SDG #2 is to “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture”

Within SDG #2 are eight targets, of which we’ll here focus on Target 2.a, which is:

Increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular least developed countries

Within target 2.a are two indicators:

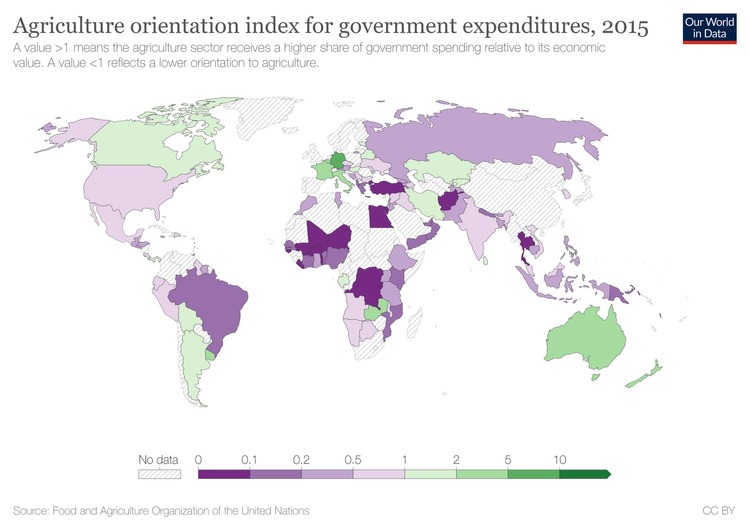

Indicator 2.a.1: The agriculture orientation index for government expenditures.

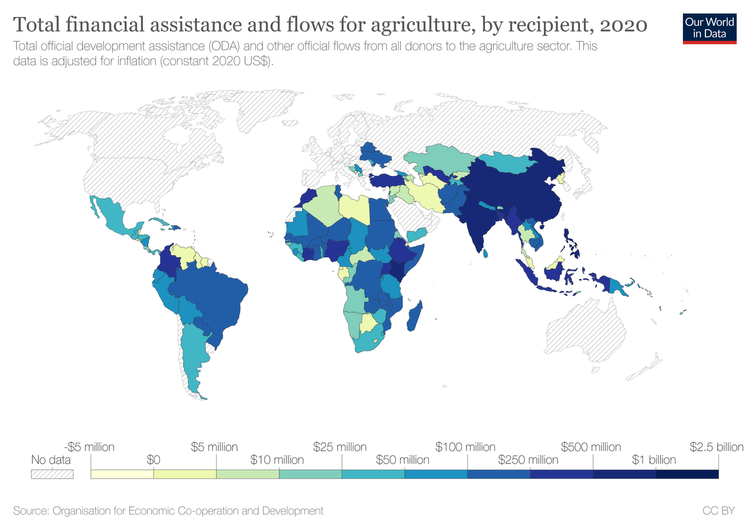

Indicator 2.a.2: Total official flows (official development assistance plus other official flows) to the agriculture sector.

Investment in general is central to the SDGs, with the implication monetary or other value is allocated with the incentive of a future return, suggesting the intergenerational aspect of the concept of sustainable development.

For the world’s most vulnerable, it’s a far stretch for most of our imaginations to suspend the ubiquity of money and finance in our daily lives to consider the lives of those tilling the soil for subsistence, far-flung from markets. For these people in such communities, the importance of their assets used for their livelihood, and the appreciation of such capital, can be life or death. Whilst in the developed world, talk of investment may bring to mind corporate profits dispensed as dividends to shareholders, for small-scale farmers, investment can mean a hand on the bottom rung of the development ladder out of penury.

But government investment in agriculture needn’t necessarily be financial. It can come in the form of investments in physical capital, such as infrastructure. For a small-scale farmer in the developing world to participate in the economy, they must be connected with markets. If the farmer lives isolated from towns and cities to reach markets, they require roads and railways. To figure out if making the trip to market is worth the bother depending on prices they can fetch, they can save themselves travelling with access to telecommunications, and electric grids to power them. The importance of rural development also ties in with SDG #9 for Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure.

Aside from investing in physical capital, governments can invest in human capital, via education among other means. Amid the context of this goal, this means educating farmers, a practice known as agricultural extension. Cutting-edge techniques, skills and tools, and the fruit of science and knowledge can be imparted to farmers to better their yield and income, and more efficiently use inputs. The agricultural revolution was humanity’s first wave of technology after all, but in the modern era, its practice can still benefit from the internet and telecommunications to better participate in the global economy, and to better manage the environment.

Also of importance are gene banks, where specimens of DNA are kept in repositories. A type of gene bank for plants are seed banks, where seeds are kept as a means of protecting genetic biodiversity in agriculture. For animals, sperm and egg cells of species are kept frozen.

For much of the developing world working in the agriculture sector, shocks from exchange rates from distant lands, fickle to the impact upon developing country food prices, can ruin lives and livelihoods. These reasons make the importance of governments acting as public investors for their own agriculture sector all the more important, as what financial profit can a private investor expect to make upon an agricultural sector in a given country which is barely productive? This would be too risky for the investor, for the smallholder would be too likely to default on any financing received.

Therefore, low-income governments need an investment strategy for agricultural development due to its centrality to rural development and poverty alleviation, and as we’ll see, statistics are central to its successful implementation.

Looking closer at Indicator 2.a.1, the Agriculture Orientation Index (AOI) for Government Expenditures is defined as the portion of government spending toward agriculture, per the Classification of the Functions of Government, divided by agriculture’s contribution to the value-added share of a country’s GDP, according to the UN’s System of National Accounts. According to this definition, ‘agriculture’ includes the forestry, fishing and hunting sectors, per Section A of the UN’s International Standard Industrial Classification of All Economic Activities (ISIC), the classification of all economic activities. Also, according to this definition, government spending is considered to be all expenditure, as well as acquiring non-financial assets in support of the agricultural sector. The data to measure this indicator on government spending is collected by an annual questionnaire by the FAO, whilst the data on value-added agricultural output originates from national accounts.

Included in government spending on agriculture for the purposes of this indicator includes policies and programs on soil improvement and mitigating soil degradation, managing animal health, research on livestock and animal husbandry; research on marine and freshwater biology, and afforestation and forestry. This spending increases the agricultural sector’s productivity and income growth, as well as increasing capital, both human and physical. The public sector is able to fill this void, commonly receiving less investment than the private sector, with the markets failing to provide for income redistribution.

For Indicator 2.a.2, we return to the topic of ODA, which we explored in the video for Target 1.a. The wording of Indicator 2.a.2 also mentions ‘other official flows’, which in the jargon of the OECD are official transactions not meeting the criteria of ODA, either because they’re not aimed at financing sustainable development, or are not concessional.

The OECD’s Development Assistance Committee identifies what specific sectors a transfer to a recipient is intended to foster, with transfers for this indicator targeted to the purposes of the agricultural sector. The OECD maintains all this information in its Creditor Reporting System, to compare where aid from DAC member countries has gone, the purpose the donor intended to serve, and which policies were used to implement such intentions.