SDG #3 is to “To ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.”

Within SDG #3 are 13 targets, of which we here focus on Target 3.3:

By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases.

Target 3.3 has five indicators:

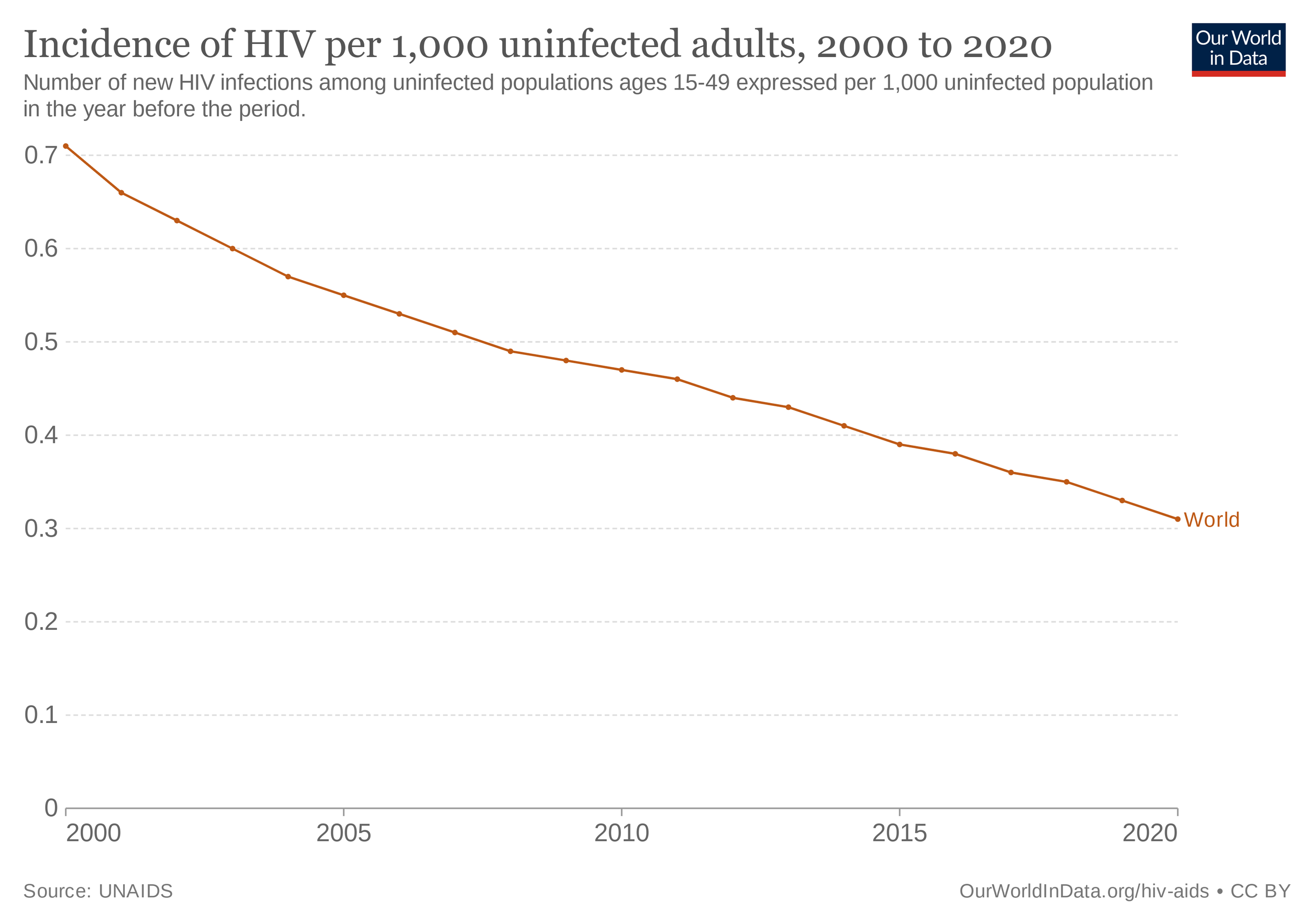

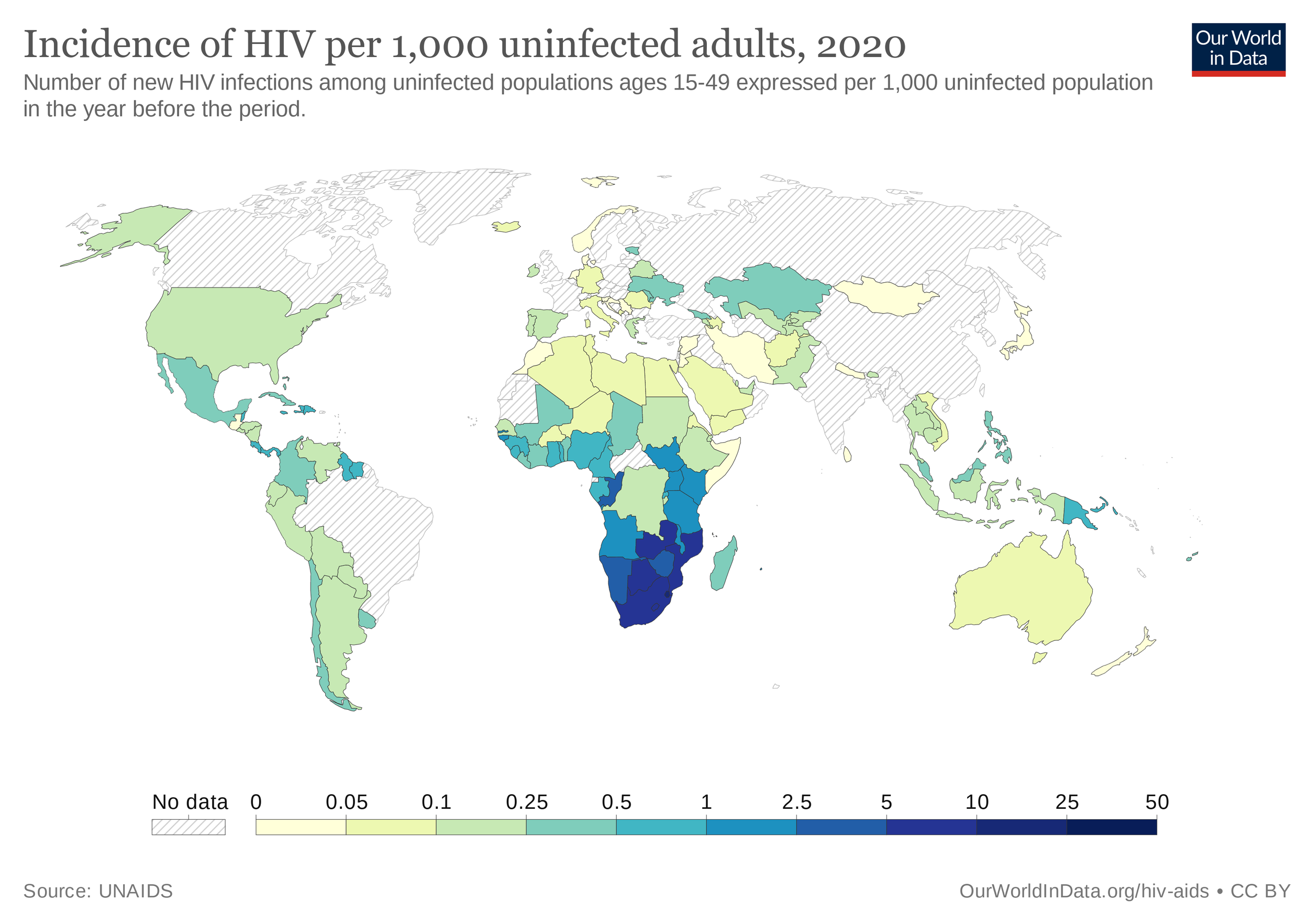

Indicator 3.3.1: Number of new HIV infections per 1,000 uninfected population

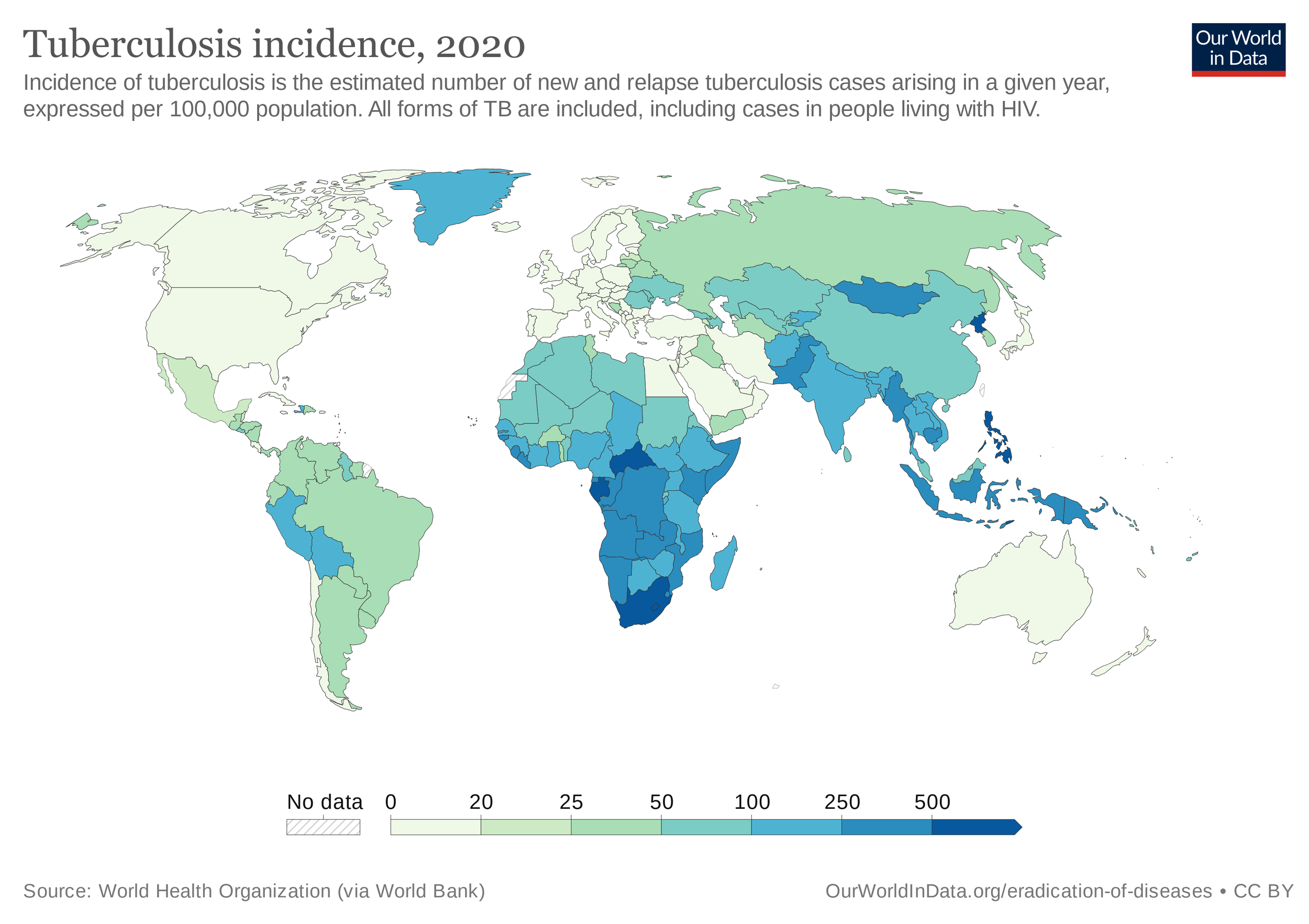

Indicator 3.3.2: Tuberculosis per 100,000 population

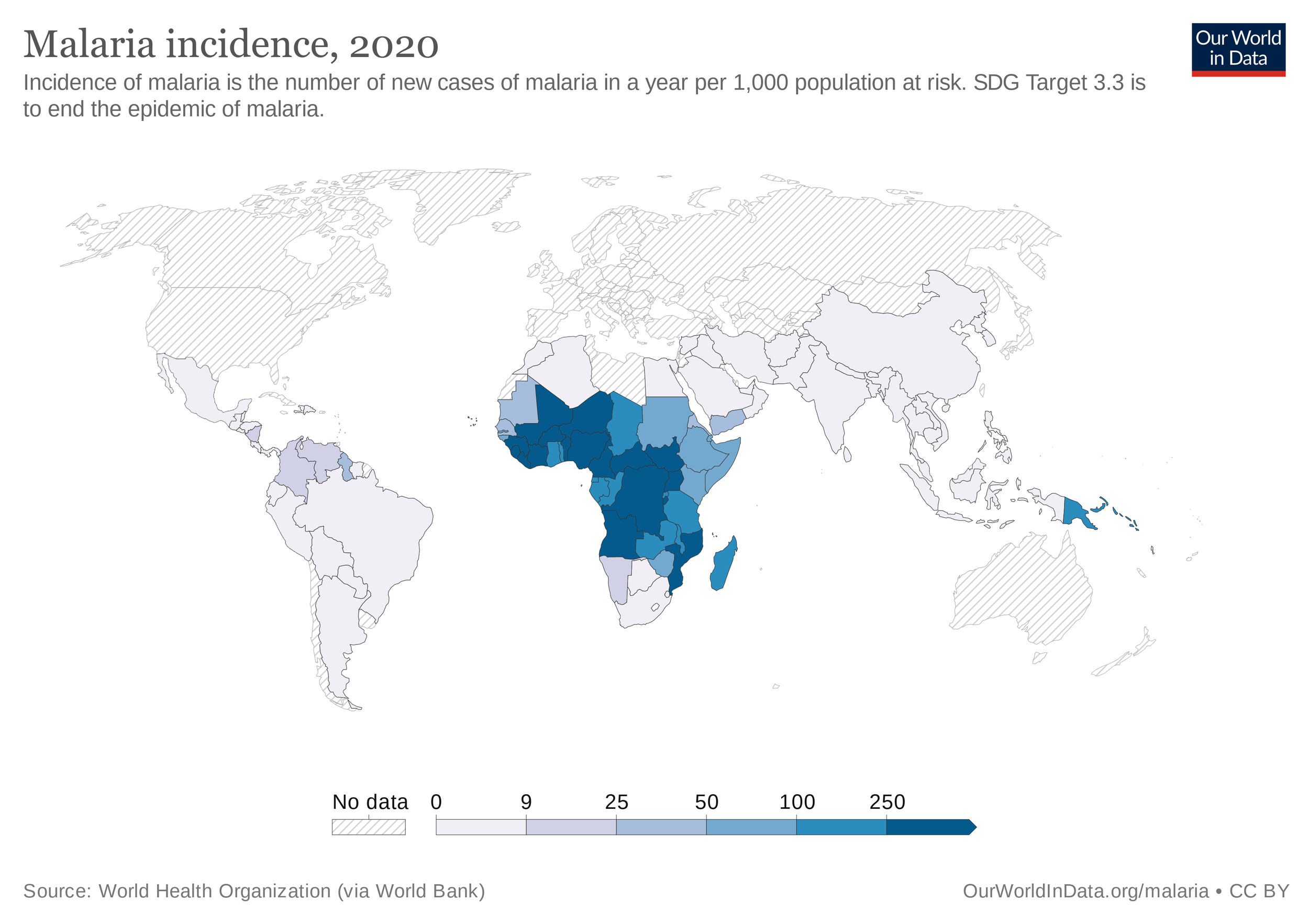

Indicator 3.3.3: Malaria incidence per 1,000 population

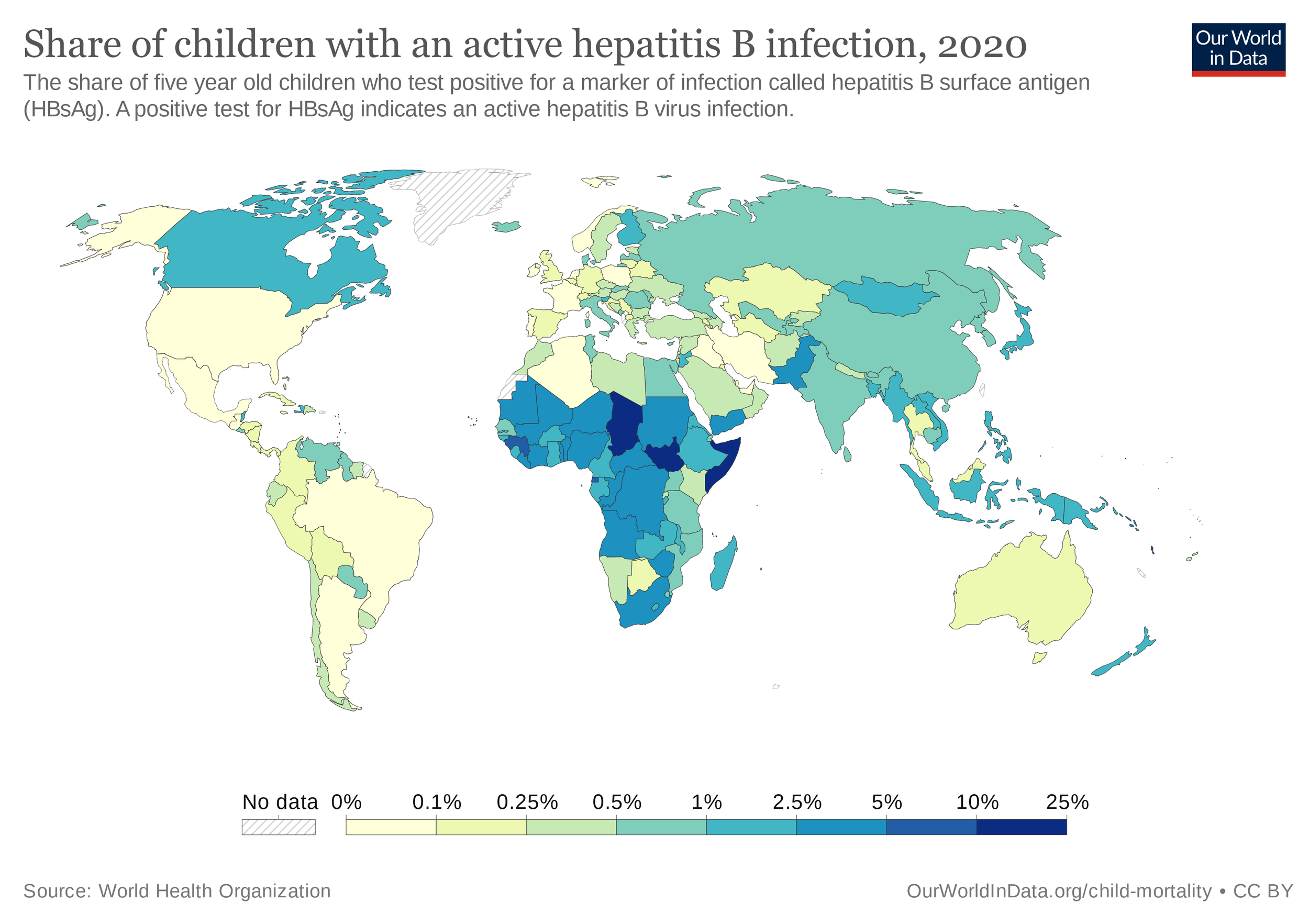

Indicator 3.3.4: Hepatitis B incidence per 100,000 population

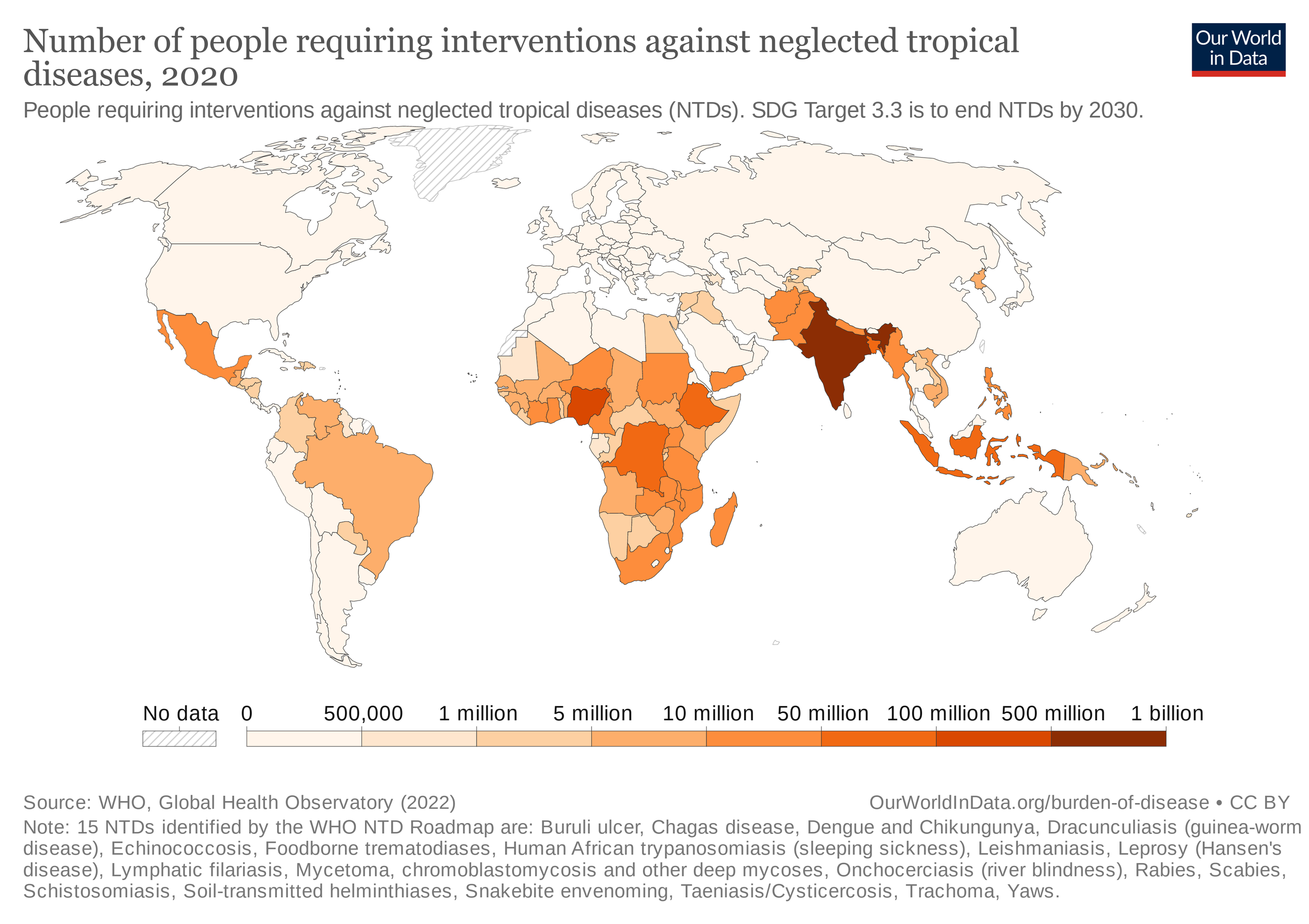

Indicator 3.3.5: Number of people requiring interventions against neglected tropical disease

Looking first at HIV/AIDS, this infection is caused by a type of retrovirus characterised by its ability to survive inside its hosts for long incubation periods. The nature of retroviruses is they copy their RNA into the DNA of a host, thus changing the genome.

The UN agency overseeing the HIV/AIDS pandemic is the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS, or UNAIDS for short, and is a joint effort of several UN agencies. 1.5 million people contract AIDS per year, resulting in 680,000 deaths in the latest year of data, with 38 million people living with the virus. A High-Level Meeting on AIDS declared the UN’s intent to end AIDS by 2030, in alignment with SDG Target #3.3. However another major pandemic, COVID-19, has slowed progress, with a current global rate of 0.19 new HIV infections per 1000 uninfected people, short of the 2030 goal for elimination of HIV.

Turning next to tuberculosis, this is caused by infection of a pathogenic bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, transmitted between people via respiratory means. The bacteria causes 10.6 million people a year to fall ill, killing 1.6 million people in 2021.

Within the World Health Organisation, the Global Tuberculosis Programme works toward ridding the world of TB from its current world level of an incidence of 127 TB cases per population of 100,000, down from 142 per 100,000 in 2015 at the start of the SDG period, and 174 in 2000, at the beginning of the MDG period. This was encapsulated in MDG #6 to “combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases”, and which aimed to halve the incidence of AIDS, malaria and TB by 2015, and reverse their incidence.

The world benefits from efforts such as the End TB Transmission Initiative, as part of the Stop TB Partnership, administered by the UN. Other impressive organisations in the fight against TB as well as AIDS, which are often co-morbidities alongside one another, include the The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, Unitaid and IFFIm, in partnership with Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance.

One of the main strategies the WHO endorses for combating TB is DOTS, which stands for directly-observed treatment, short course, whereby a healthcare worker watches the patient take their dose. Immunisation with a TB vaccine is a widespread method of prevention. However, hampering global efforts to control and prevent TB are strains of TB resistant to drugs developed to treat the disease.

Alongside AIDS and TB, in 2020 there were 241 million cases malaria, resulting in 627,000 deaths. The mosquito-borne disease affects Africa to a disproportionate level, where it’s home to almost all cases and deaths. In the effort to end the malaria pandemic, the world is still shy of the mark, with an incidence of 59 new cases per 1,000 of the global population.

The following indicator focuses upon hepatitis B. Hepatitis is a disease characterised by inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B is a viral type of hepatitis, caused by infection of the hepatitis B virus. Immunisations are an effective tool deployed worldwide to prevent the spread of the hepatitis B virus. The world isn’t too far away from eliminating this disease, with less than 1% of children under-5 worldwide testing positive for an active case of hepatitis B.

For the final indicator of this target, we look to neglected tropical diseases, which are infectious diseases common to developing countries in the tropics and subtropics of Africa, Asia and the Americas. So what are these neglected tropical diseases we’re aiming to control by 2030?

These include about 20 infectious diseases, so let’s parse through some which may be less than household names, many of which are water-borne diseases:

Lymphatic filariasis is caused by parasitic worms, microscopic in size, affecting the lymphatic system.

Schistosomiasis is another infection caused by parasitic worms

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis is a disease caused by another parasitic worm, in this case observable to the human eye, infecting the intestines, and transmissible via soil contaminated by these type of worms called helminths

Onchocerciasis, a disease of the eyes and skin, also caused by a worm

Buruli ulcer, an infection of the skin caused by a type of bacteria

Chagas disease, transmitted via a bug carrying a parasite called Trypanosoma cruzi

African sleeping sickness, also known as human African Trypanosomiasis, is similar to Chagas. Both are due to parasites belonging to the genus Trypanosoma, in this instance the species Trypanosoma brucei.

Leishmaniasis, a parasite spread by sandflies

Mycetoma, a bacterial and fungal infection, spread by the skin’s exposure to soil or water containing the bacteria or fungus causing this disease

Yaws, a chronic skin infection, resulting in small lumps and ulcers on the skin

Dracunculiasis, caused by the worm-like parasite species Dracunculus medinensis, also known as Guinea worm, so named because of the Gulf of Guinea in West Africa, where it was once prevalent.

Echinococcosis, caused by parasitic worms of the genus Echinocococcus.

Also included among the neglected tropical diseases, is snake envenoming, caused by the toxins from a snakebite.

Various medications treating infection by some of the aforementioned parasitic worms include diethylcarbamazine, albendazole, mebendazole and praziquantel.

One of the preventive strategies endorsed by the WHO for some of the neglected tropical diseases caused by helminth worms is preventive chemotherapy, which is the safe administration of a medicine to a whole population susceptible to infection by these worms.

Progress made in lowering the number of people requiring interventions against neglected tropical disease has been slight over the span of the SDG period, down only 60 million since 2015 to its current total of 1.73 billion.

As with all SDG #3 targets, the provision of universal health care is a catch-all solution to almost all facets of achieving health and well-being for all, including ending the epidemics at the core of Target #3.3.