In this episode, we’re joined by Guillaume Lafortune, Vice President and director of the Paris office of the SDSN, the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, under the auspices of the UN. Guillaume also coordinates, and is a co-author, of the SDSN’s Sustainable Development Report, published each year since 2016

Dominic Billings: Guillaume, what was your path to your current career? I know that you studied Economics and Public Administration in Quebec. But what was your path to where you are now?

Guillaume Lafortune: Well as you said, Dominic, I’m an economist by training. I've always been also interested in public policies. I would say, at large. Did a very classic path from a school of public administration to entering government, the Ministry of Economic Development, in Quebec, Canada, working with small and medium enterprises, and trying to see how we can support them in scaling up, and including looking at international opportunities also abroad, Quebec being a small market. There's always this idea that it's important also for Quebec companies to be in touch with what's going on elsewhere in the world. So, both this sort of focus on economics, but also the international dimension, has always been sort of part of my background, and broad interest in public policies.

And then I think the other thread would be I’ve always been interested in doing research. But doing research that you can actually present to those that are eventually taking the decisions. That's why, for me, it was very good to enter, after my experience in government, to join the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris, where you do a lot of statistical analysis studies. But then you do present to the people in their governments, who are in charge of the respective portfolio? Whether it is about governance reform - I've worked quite a bit in the Public Governance department - but also, people in charge of the environmental portfolio in their country, education, health, and so on. You do present your studies to those that make decisions.

And finally, that's also the link with my current work at the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, since we are a network of scientists that try to establish this sort of link with policymakers, with the UN system. We've been the knowledge brokers between what science is saying we should do, some of the solutions that science can bring, and also what the UN System and national governments can do. So, this focus on science on one side, but also the direct connection with decision-making, has always been an important part, I would say, in my career.

Dominic Billings: You're one of the co-authors of the SDG Index - now titled the Sustainable Development Report. What was the story behind the formative stages of that? I know you collaborated with Guido Schmidt-Traub in particular, and Christian Kroll, one of the progenitors of the original. What was that process like in the very beginning for you?

Guillaume Lafortune: So, in a nutshell, what the SDG Index does is, every year we track the performance of all the UN Member states on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. These are the goals that have been adopted by the international community, actually by all UN member states, back in 2015. We have to remember that this is the only comprehensive vision adopted internationally that looks at both social and economic progress, but also environment, climate, biodiversity and governance issues. So, it's a very comprehensive framework. There are 17 goals, 169 targets, and what we do at the SDSN, working of course with partners, is to look every year how countries are performing on those 17 SDGs. So, in terms of major stages, at the very beginning when we started doing this, there were really a lot of technical questions that needed to be resolved. Which indicators do you select? How do you aggregate across goals? How do you create an overall ranking, scoring and so on. So, we did quite a bit of work, both internally, but also in making sure that we were getting the necessary external checks to ensure that was scientifically robust

So, we were peer reviewed by Nature Geoscience, Cambridge University Press, but also, we got in touch with the European Commission, and said, “Could you do a statistical audit of that report, because we really want to make sure that we're doing this right?” And also, that effort of comparing our results, via-a-vis other assessments that are being done by other organizations to really understand why, for certain Goals, our assessment was slightly different than what the OECD is presenting, or what Eurostat is presenting, for instance. So, the first step was really to make sure we were doing it right, and now the methodology is stable - we've been doing this since 2016-2017, so it's been a couple of additions now - it's really about how do we connect the findings with policy messages and the broader discussions around “How do we finance this agenda?”. One illustration of that second phase is we move from the report, which was called the ‘SDG Index’, to a report which is now called the ‘Sustainable Development Report’, because there is more than SDG Index. The Index remains the backbone, but there's much more policy discussions and sections.

Dominic Billings: How do you feel about the progress of the SDGs? The data and the report speak for itself, but on a personal level, how do you feel?

Guillaume Lafortune: Well, first of all, I continue to think that it is an incredible idea. This idea that we establish goals for humanity as a whole, that called for eradicating extreme poverty; hunger; access to social protection; healthcare and education for all; fight against income and wealth inequalities; access to water and sanitation, and then also move towards responsible consumption and production; climate action, and then strengthening institutions and international partnerships. I continue to think that this is an incredible idea, and it's the first time in human history that we were able to agree on a common set of goals.

Despite differences in cultures, history and approaches to economic and public policy, all governments around the world managed to say “These are goals we should all be pursuing”. I really hope that this idea of goal-based development can continue. Obviously, now we should maintain our effort to try to do major breakthroughs on this Agenda until 2030. But then beyond 2030, I think it will be very important to also have an agenda that continues this sort of goal-based development.

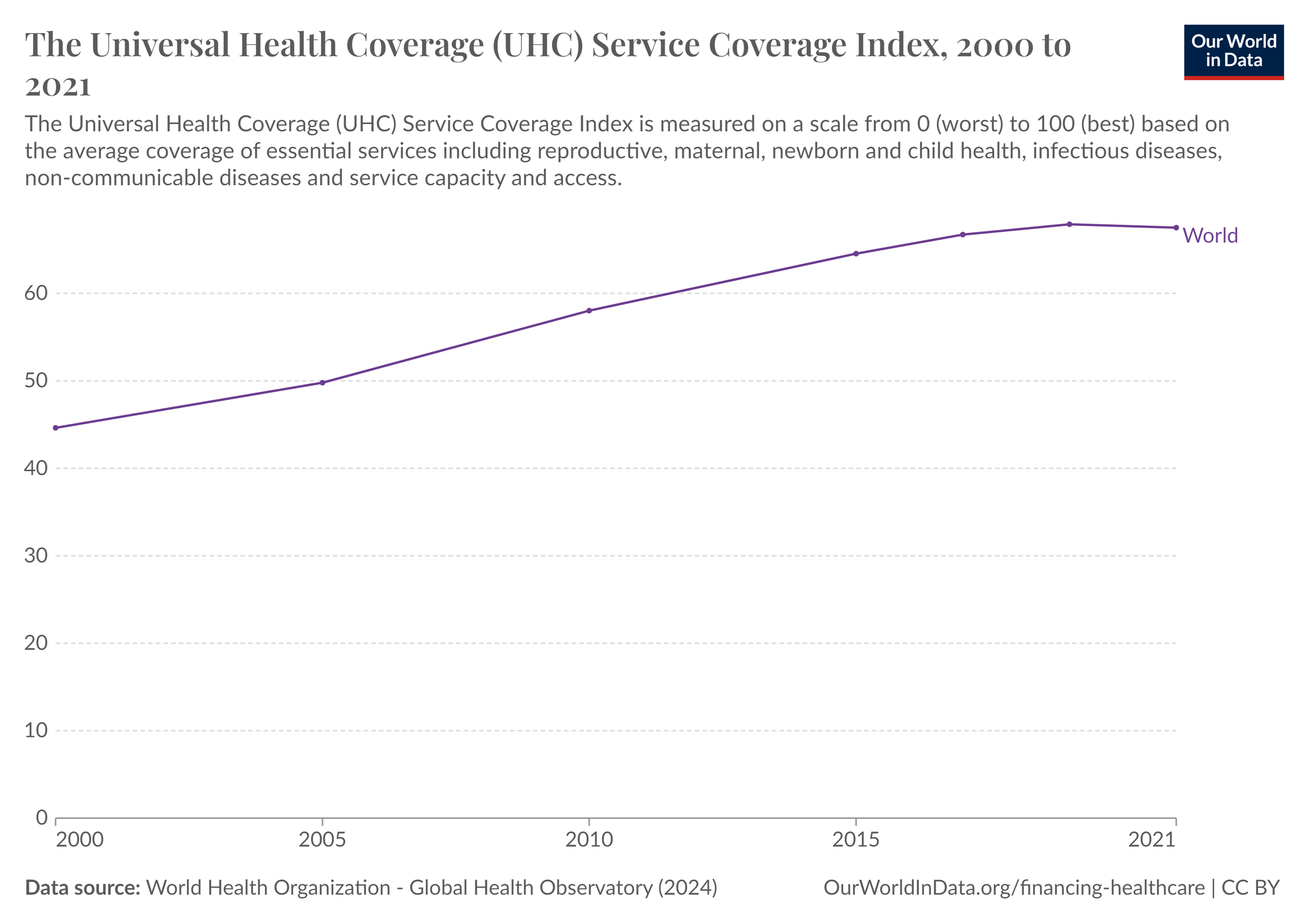

In terms of how the world is doing on the Sustainable Development Goals, it's very clear that the multiple crises we've been facing - from COVID-19, geopolitical tensions, security crises, now inflation, probably recession in many parts of the world, which is to come, budget pressures - these led to major setbacks and reversal in SDG progress. So, we were seeing overall, from the moment the SDGs were adopted to 2019, the world was making progress year-on-year. The overall SDG Index was progressing year-on-year until 2019, which was notably led by progress in some of the countries and regions in the world that were starting from very low points on the SDGs. So major progress in terms of fighting extreme poverty, for instance. But also access to basic infrastructure and services as well. Even before COVID-19 hit, we were still saying progress was too slow, certain Goals were not moving in the right direction, and there were major disparities across countries. But on average, the world was progressing on this Agenda. Since 2020, worldwide, we do not see any more progress on this agenda.

It's stagnated and even reversed in progress in many parts of the world. What's a little bit sad is that reversal in progress is happening in particular in countries that are poor and vulnerable, and did not have the ability, for instance during COVID-19, to mobilize large amounts of money to finance the urgent expenditure related to the pandemic - but also, those recovery plans, as we have been able to do in a lot of the high-income countries. That's why all those international summits have happened -we're right after COP 27, there was an important G20 meeting also a few days ago - but also, we're heading towards a Heads of State Summit on the SDGs in September 2023.

These are all very important to recognise where we've made progress since 2015 - because we're at halftime now in this agenda. But also come up with solutions and renewed commitments on how we are going to restore and accelerate SDG progress over the next couple years?

Dominic Billings: You mentioned what was the ‘SDG Index’ is now been expanded to the ‘Sustainable Development Report’, and one of the features of the most recent report was financing, and another was spillover effects, of which the SDSN, with you as co-author, have published many reports, including as recent as this week

What about spillover effects requires the focus you’ve given it?

Guillaume Lafortune: The basic idea behind the spillover effects is, if we consider the SDGs as a global responsibility, and if countries aim to decarbonise their energy system and move towards more responsible consumption and production, the decarbonisation effort should not be achieved by outsourcing high-emitting sectors - whether it's cement or steel - to another country, and then re-importing production, so the emissions happen outside of our borders.

So, on paper, everything looks good. We're” moving forward” in terms of decarbonising our economy, but in terms of overall carbon emissions, these are being outsourced and they happen elsewhere. The idea behind spillover effects - to capture those impacts embodied into trade and consumption. There are other types of spillover effects - for instance, financial flows and financial spillovers e.g., tax evasion, profit shifting, unfair tax competition, that can undermine the ability of other countries to mobilize resources to, to move towards those Goals.

And so, as you said, Dominic, at the SDSN, we've always considered integrating those spillover effects. Again, considering the SDGs are a global responsibility, and it makes no difference for climate change whether greenhouse gas emissions are generated within a country’s borders, or in another country for satisfying production.

And by the way, that explains also why our results can sometimes be different from other assessments, because we include those types of indicators. On the spillover aspect, it's not only about environmental spillovers, but increasingly we also document deforestation embodied in our consumption. We also look at how much consumption, especially in rich countries, is leading to resource depletion, including water scarcity, in the rest of the world - but also social impacts. So, we're able to track now that each year, through the consumption of textile products, there's about 400 people that die in the world to satisfy the European Union's consumption of textile, and more than 20,000 people that have non-fatal accidents at work. We released a study earlier this week where we've identified that each year European consumption is associated with 1.2 million cases of forced labor around the world.

And we did a deep dive into fossil fuels and mineral materials, which is one of the supply chains where those impacts happen. So, the point here is to say, we need to track the effect we have through consumption, and we also need to adopt policies to curb those spillover effects and work with partner countries so we reduce our global footprint from consumption.

Dominic Billings: You mentioned the recent UNFCCC COP in Sharm El Sheik, but I know you’re going to the Convention on Biological Diversity in Montreal. The Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC is enmeshed as part of SDG 13, but the ethos of the Convention on Biological Diversity underpins SDG 14 and 15. How do you feel about the outcome of COP 27 in Sharm El Sheikh, and how do you feel about the forthcoming CBD COP in Montreal?

Guillaume Lafortune: On the COP in Egypt, the outcome is mixed. On the positive side, there's been quite a good breakthrough when it comes to recognizing some of the historical responsibilities, in terms of emissions for climate change, and the fact we need to move into a financial mechanism to share more fairly globally, the costs of losses and damages related to natural and climate events. But also, the costs of adapting infrastructure especially, so the most vulnerable countries that are often not responsible for climate change, can finance losses and damages and adaptation. So, at least the political consensus that emerged this year is a move in the right direction. The major aspect where we're not seeing enough progress is commitments, pledges and trajectories on the mitigation side, in terms of accelerating the decarbonization of the production system and economies globally.

So that remains an important loophole, and it's becoming, you know, harder and harder to stick to that 1.5-degree objective, as part of the Paris Climate Agreement. But on the biodiversity side, it's also really important. On the climate side, we have the Paris Climate Agreement - a global target has helped to mobilize actions, energy and momentum around that goal.

The fact that we don't have the equivalent of a Paris Climate Agreement for biodiversity might explain why we're still a little bit lagging behind when it comes to global actions on biodiversity. The numbers are terrible when it comes to biodiversity loss, deforestation, and so on. To give a very practical example, when we look at the bees, 70% of what we eat requires pollination. So, as we see the number of bees dropping, there's a real question around, “What are we gonna do?” This is where I'm not sure innovation and progress - for instance, replacing bees with drones - will really help us out. It's really an issue around how do we prevent this from happening, and how do we also put a price on the natural services that nature is providing?

So, there's big discussions right now around pricing the natural services. But beyond that, I really hope Montreal can become for biodiversity what Paris has been for climate.

So big hopes for the biodiversity conference in Montreal, and it's very important, because we see it every year when you do the SDG Index. The biodiversity indicators are really not moving in the right direction at all.

Dominic Billings: Guillaume, on a personal level, if you trace your life from maybe the beginning of your tertiary education through to now, what's driven you? What's brought you to where you are now a person?

Guillaume Lafortune: I've always wanted to try to work for the common good. At least do my best to do something that has a positive impact on the world. Now I have two kids - they're very young, a small baby and a four-year-old - but in 10 or 15 years, when I’ll be explaining to them what I'm doing professionally, I'll be able to demonstrate or show them I've done my best.

So, they can live in a world where you have opportunities, you are safe. You're not being hit by droughts and heat waves and natural disasters all the time. We live in a world where there's partnerships, where the multilateral system is able to address some of the challenges of our time. So, all of those things, in my view, can help, and address those big challenges. My hope is to have a positive impact by making that connection between what science and data evidence tells us.

This is important, in this post-truth era, and fake news and so on, to try to have groups of people and networks of scientists, that can try to bring the evidence to the policymakers, and then see how we can move forward on those Sustainable Development Goals.

Dominic Billings: Thank you so much, Guillaume, for your time - so appreciative. I feel like both yourself and the co-authors of the Sustainable Development Report in particular have done as much for sustainable development, and the SDGs, then anyone.

Guillaume Lafortune: Thank you very much, Dominic.